Week 9

Trumpism

SOCI 229

Lecture I: October 28th

A Quick Reminder

Response Memo Deadline

Your sixth response memo—which has to be between 250-400 words and posted on our Moodle Discussion Board—is due by 8:00 PM today.

A Quick Reminder

Midterm Paper

Midterm Paper Deadline(s)

If you have yet to submit your midterm paper, it is due by —

- 8:00 PM on Friday, November 1st

A Quick Reminder

Midterm Paper

To submit the paper, visit the following page on Moodle.

A Quick Reminder

Midterm Paper

Please submit the paper as a .docx or .doc file.

A Quick Reminder

An Election Is Looming Over the Horizon

Some News

Dr. Stephanie Ternullo will be joining us on November 13th.

Some News

Dr. Miloš Broćić will be joining us on December 11th.

A Brief Aside

My Trip to Florida

Today’s Focus—

The Supply Side of Trumpism

What is Trumpism?

A concept that has been heavily contested for nearly a decade.

What is Trumpism?

What is Trumpism?

Prior to the 2016 Presidential Election, Mudde (2018) argued1—

“Trumpism” is far too big a term for the incoherent and ever-shifting views of Trump. It is impossible to discern an ideology that Trump adheres to. He never developed a real ideological platform and has been inconsistent on core issues — from pro-choice to anti-abortion, from pro-universal healthcare to anti-Obamacare, etc. However, his current popularity does seem to be based on a combination of features that defines Europe’s contemporary populist radical right: nativism, authoritarianism, and populism.

(Mudde 2018, 32, EMPHASIS ADDED)

What is Trumpism?

Later, Mudde (2018) posited1—

Although “Trumpism” is not a particularly coherent or developed ideology, it has some consistent and dominant ideological features. Its core is a combination of nativism, authoritarianism, and anti-establishment sentiments, which is very similar, though not identical, to the core ideology of the European populist radical right … While he shares nativism and authoritarianism with the European radical right, this is not the case for populism … Trump does argue that “the elite” are all corrupt and the same, but he does not exalt the virtues of “the (pure) people.”

(Mudde 2018, 49, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Group Discussion I

Do You Agree With Cas Mudde?

In groups of 2-3, discuss —

How would you conceptualize Trumpism?

Is populism a key ingredient? Why or why not?

More broadly, do you agree with Cas Mudde’s assessments of what Trumpism-as-inchoate-“ideology” represents?

A Different Treatment

What is Trumpism?

Lieberman and colleagues (2017) define Trumpism as —

[A] political orientation that challenges the interlocking liberal commitments to a relatively interventionist state, economic openness, cultural and political pluralism, and internationalism.

(Lieberman et al. 2017, 9, EMPHASIS ADDED)

What is Trumpism?

Is Trumpism really unique?

Contextualizing Trumpism

Yes —

at least according to Lieberman et al. (2017).

Contextualizing Trumpism

One of the alarming characteristics of Trumpism is its order-shattering character. From this point of view, Trumpism challenges a generally coherent and internally self-reinforcing global liberal order that has framed American politics for decades: how may a presidential candidate behave, what institutions are legitimate and why do we believe them, who may legitimately participate in American political life, and what is America’s place in the world?

(Lieberman et al. 2017, 9, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Contextualizing Trumpism

A Question

Would Cas Mudde agree?

Contextualizing Trumpism

Yes and no.

Contextualizing Trumpism

Trump stands in a long US tradition of right-wing businessmen who present themselves as saviors of “the American way” and who can attract cross-class coalitions of supporters—including, among others, Henry Ford, Robert W. Welch Jr, and Ross Perot. Trumpism also shares many features with distinctly American ideologies, expressed through organizations like the Know Nothings in the mid-19th century, George Wallace in the mid-20th century, and the Tea Party movement in the early 21st century.

(Mudde 2018, 50, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Contextualizing Trumpism

Review — from SOCI 231

What is Trumpism?

At the same time, Trump is unique, in both a contemporary and historical American and European context, in that he is an anti-establishment “outsider” who mobilizes through an establishment party. This aspect is often underemphasized, particularly by the obsession with European comparisons. Berlusconi and Le Pen had to fight to get into the political mainstream, while Trump’s fight was from the start within the political mainstream. It was largely because he was running within the GOP primary race that he received the generous media attention — it is doubtful he would have received anything near that attention had he entered the race as an independent third-party candidate.

(Mudde 2018, 50, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Contextualizing Trumpism

Consider two data points from Karim and Lukk’s The Radicalization of Mainstream Parties in the 21st Century —

| country | year | party | leader | far right typicality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States of America | 2012 | |||

| United States of America | 2016 |

Contextualizing Trumpism

Trumpism may be relatively unique for another reason.

Contextualizing Trumpism

Since the 1970s, the two parties have coalesced around divergent ideological and programmatic poles, again lessening the centripetal forces that once contributed to stability and moderation … The rise of Trumpian populism in the context of such heightened partisan and ideological polarization is a comparative anomaly. In Europe and Latin America, recent expressions of populism — of both left- and right-wing varieties — have emerged when citizens were detached from mainstream parties that had progressively converged in their platforms and policies.

(Lieberman et al. 2017, 14, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Contextualizing Trumpism

Populism typically thrives where partisan identities in the electorate have withered and major parties lose the capacity to “sort” voters into rival camps. Indeed, populism often feeds off the inability of voters to differentiate among mainstream parties that adopt similar policies and seemingly collude in managing the state; such convergence and collusion make it easier for people to lump established parties together in an undifferentiated casta politica (political caste), and then construct an “antagonistic frontier” between this leadership cast and “the people.”

(Lieberman et al. 2017, 14, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Contextualizing Trumpism

In the United States, however, Trumpism emerged at a time when partisan identities, ideological differentiation, and organizational animosities were all at elevated levels. Moreover, it emerged in a political system uniquely designed, as we have noted, to fragment and disperse power, with multiple “veto points” where policy change can be blocked or frustrated.

(Lieberman et al. 2017, 15, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Group Discussion II

Trumpism as a Sui Generis Phenomenon?

In new groups, answer a “simple” question—

i.e., is Trumpism unique?

Trumpian Rhetoric

Exclusionary Discourse

[P]opulism and low national pride were not unique to Donald Trump’s radical-right discourse; on the contrary, these frames have been commonplace in U.S. presidential politics, typically among political challengers. In contrast, the 2016 and 2020 Trump campaigns’ explicit appeals to an exclusionary conception of American nationhood were unusual: no other party nominee for the highest office had been as unabashed in portraying immigrants and ethno-religious minorities as illegitimate members of the nation.

(Bonikowski, Luo, and Stuhler 2022, 1724, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Boundary-Making

Trump brought the politically marginalized white working class back to the voting booth by cultivating differences … that is, by reinforcing the boundaries drawn toward socially stigmatized groups. This was accomplished by repeatedly insisting on the moral failings of these groups (in the case of refugees and undocumented immigrants) as well as by making these groups more one-dimensional, by stereotyping them as in need of protection (for African Americans and women) … Thus, Trump acted as an influential cultural agent who knew how to tap into latent and less latent symbolic boundaries that already existed among white working-class Americans in the early 1990s.

(Lamont, Park, and Ayala-Hurtado 2017, S173, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Boundary-Making

A Question

Think back to Week 7.

What kind of boundary-making strategy maps onto Trump’s discursive tactics from 2016?

Boundary-Making

Ressentiment

Trump transforms short-lived yet intense emotions such as anger, along with paradoxical investments in the concept of white victimhood, into nearly inexhaustible rhetorical resources … Trump’s claims of victimhood and anger-laden calls for revenge seek out what philosopher Max Scheler called “the man [sic] of ressentiment,” or an audience who is seething with righteous anger and envy yet also suffering from the impotence to act or adequately express frustration.

(Kelly 2020, 4, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Ressentiment

Ressentiment encourages individuals to divest from the civic good and ennoble their own suffering, however mundane or contrived. Ressentiment prevents subjects from moving forward because their gaze is cast backward toward re-experiencing an injury. Trump directs his audience’s anger toward settling old scores, litigating past wrongs, and resurrecting new enemies. In the case of Trump’s audience, the collective injury is those social and economic changes that have supposedly displaced white America. He creates a political community forged through and invested in its own marginalization.

(Kelly 2020, 19, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Trump’s Rhetoric in a Nutshell

A Question

How would you describe Trump’s rhetoric or discourse?

Group Discussion III

Trumpism and the GOP

Did Trump radicalize the Grand Old Party? Or is he the consequence of GOP radicalization? Alternatively, is this question—implicitly invoked by Mudde (2018) in The Far Right in America—unwarranted?

Lecture II: October 30th

A Quick Reminder

Midterm Paper

Midterm Paper Deadline(s)

If you have yet to submit your midterm paper, it is due by —

- 8:00 PM on Friday, November 1st

A Quick Reminder

Midterm Paper

To submit the paper, visit the following page on Moodle.

A Quick Reminder

Midterm Paper

Please submit the paper as a .docx or .doc file.

Today’s Focus—

The Demand Side of Trumpism

Who Supports Trump?

Any takes?

Who Supports Trump?

Data from PresElectionResults package.

Who Supports Trump?

Who Supports Trump?

Who Supports Trump?

Who Supports Trump?

Group Exercise I

Interpreting the Data

In groups of 2-3, explore the data available via—

What do the data tell you about the demand side of Trumpism?

Moreover, what do these data not give us insight into?

Cultural Underpinnings

American Political Culture and Trump

What are the cultural factors underlying Trumpism as a

mass social movement?

American Political Culture and Trump

Scholars have furnished many candidate explanations.

Loss, Deprivation and Emotion

Since 1980, virtually all those I talked with felt on shaky economic ground, a fact that made them brace at the very idea of “redistribution.” They also felt culturally marginalized: their views about abortion, gay marriage, gender roles, race, guns, and the Confederate flag all were held up to ridicule in the national media as backward. And they felt part of a demographic decline; “there are fewer and fewer white Christians like us,” Madonna had told me. They’d begun to feel like a besieged minority.

(Hochschild 2016, 221, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Loss, Deprivation and Emotion

Trump is an “emotions candidate.” More than any, other presidential candidate in decades, Trump focuses on eliciting and praising emotional responses from his fans … His supporters have been in mourning for a lost way of life. Many have become discouraged, others depressed. They yearn to feel pride but instead have felt shame. Their land no longer feels their own. Joined together with others like themselves, they now feel hopeful, joyous, elated. The man who expressed amazement, arms upheld—“to be in the presence of such a man!”—seemed in a state of rapture. As if magically lifted, they are no longer strangers in their own land.

(Hochschild 2016, 221, EMPHASIS ADDED)

White Identification

[A] great deal of many whites’ reactions to our country’s changing racial landscape do not simply manifest in outward hostility. Amidst these changes, many whites have described themselves as outnumbered, disadvantaged, and even oppressed. They have voiced their anxiety over America’s waning numerical majority, and have questioned what this means for the future of the nation. They have worried that soon they may face discrimination based on their own race … As a result … racial solidarity now plays a central role in the way many whites orient themselves to the political and social world.

(Jardina 2019, 5, EMPHASIS ADDED)

White Identification

In 2012, the evidence is straightforward; whites high on racial identity were far more supportive of Mitt Romney. Even more significantly, in 2016, we can explain the unconventional, yet successful candidacy of Donald Trump through the lens of white identity and consciousness. Trump, who ran on an anti-immigrant, pro-Social Security platform, in many ways uniquely appealed to whites who were anxious about their group’s waning status. It is, perhaps, entirely unsurprising that white identity and consciousness were two of the best indicators of support for Trump.

(Jardina 2019, 19, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Outgroup Derogation and Antipathy

[W]e identified a unique and powerful predictor of (Trump’s) popularity—animus toward Democratic-linked and traditionally marginalized groups. As the Republican Party grows increasingly white, Christian, and male, it may be tempting to explain Trump’s appeal with partisanship alone. However, that is not the case in these panel data. Trump appears to have been uniquely able to attract support based on preexisting animosity toward these groups. The same cannot be said for other Republican Party officials or the Republican Party itself. Similarly, we find no such pattern among Democratic officials or the Democratic Party.

(Mason, Wronski, and Kane 2021, 1515, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Outgroup Derogation and Antipathy

Figure 6 from Mason, Wronski and Kane (2021)

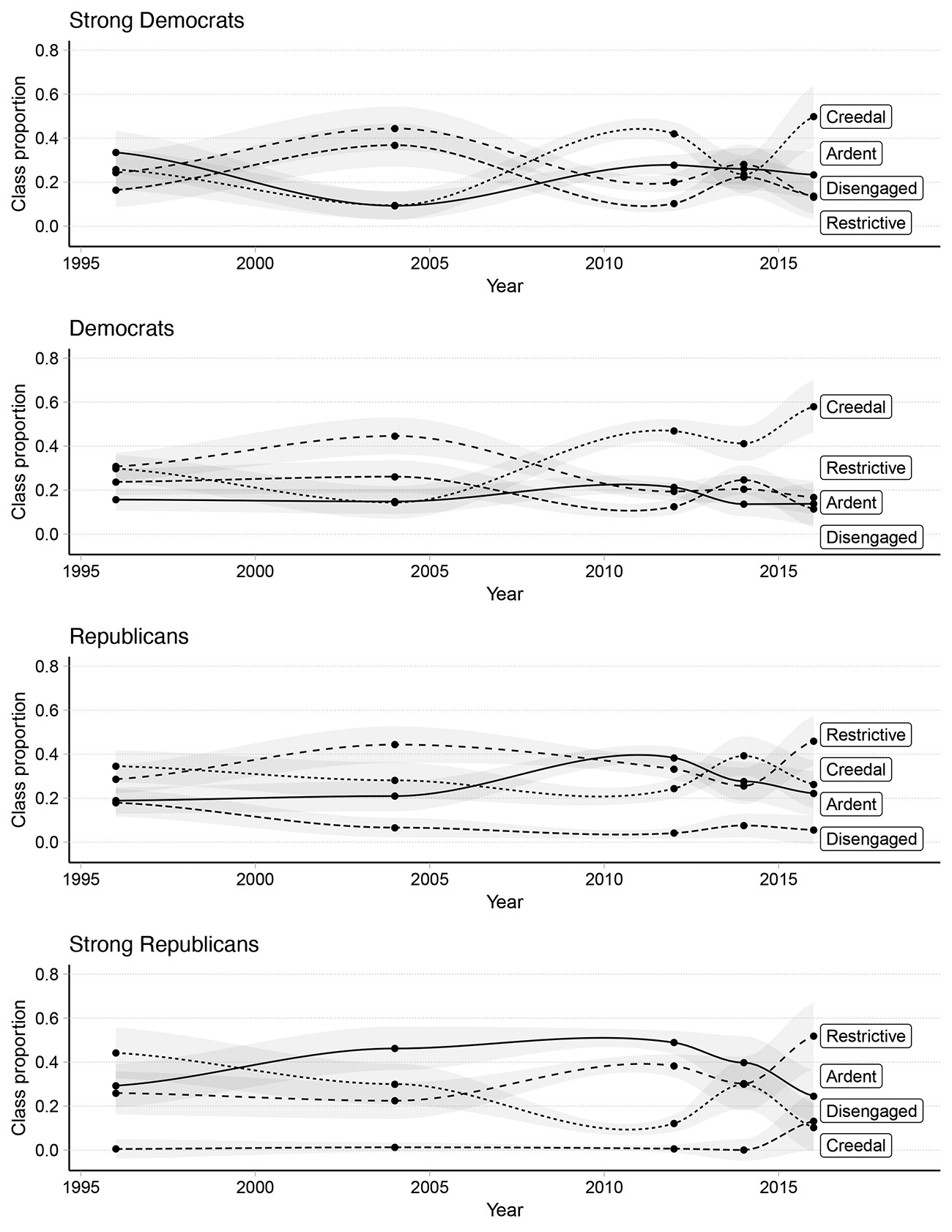

Exclusionary Nationalism

[T]he importance of nationalism in the 2016 election did not result from a sudden surge in the types of nationalism associated with Trump support. On the contrary, popular conceptions of nationhood, on average, were quite stable between 1996 and 2016 (although 2004 and 2012 marked temporary deviations from this trend). This does not imply, however, that public opinion trends were irrelevant for Donald Trump’s success. What our analysis reveals is that over the same time period, Americans’ nationalist beliefs became increasingly mapped onto their partisan identities. By 2016, most Republicans adhered to restrictive or ardent nationalism, while most Democrats espoused creedal nationalist beliefs.

(Bonikowski, Feinstein, and Bock 2021, 530, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Exclusionary Nationalism

Click to Expand

Figure 6 from Bonikowski, Feinstein and Bock (2021)

Misogyny

(Red Pills’) [m]oderators and elite users pitted Clinton and Trump against each other ideologically and argued that Clinton would exacerbate the war on men. The top Men’s Right’s post of October 2016, titled “‘Sexual Assault’ Is Why I’m Endorsing Donald Trump for President of the United States,” was created as a call to action against this political development. In this post, moderator “redpillschool” explains that this war on men “is not abating as many have suggested over the last few years. It’s growing, and it’s growing out of control.” He takes care to note that while the forum is normally “politics neutral,” the 2016 election represents a key political opportunity for Red Pill users, one that could make or break their ability to push back against feminism.

(Dignam and Rohlinger 2019, 603, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Mendacious Truth-Teller

[W]hen voters identify with an “aggrieved” social category—that is, one whose members see themselves as unfairly treated by the political establishment, they will be more motivated to view demagogic falsehoods from a candidate claiming to serve them as gestures of symbolic protest against the dominant group. When this happens, such voters will view the candidate making these statements as more authentic than would people in other social categories.

(Hahl, Kim, and Zuckerman Sivan 2018, 9, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Mendacious Truth-Teller

How could a candidate who repeatedly told lies and flagrantly broke norms be viewed as authentic by his supporters? One possibility is that his supporters thought his false statements were true … [O]ur post-election survey … demonstrates that most Trump supporters recognized one of his most notorious lies as false, and that the key difference between Trump voters’ and Clinton voters’ perceptions of this lie was that the former viewed it as a form of symbolic protest. Moreover, Trump voters’ tendency to perceive this symbolic protest was significantly correlated with their tendency to see him as authentic and to be enthusiastic in their support for him.

(Hahl, Kim, and Zuckerman Sivan 2018, 24, EMPHASIS ADDED)

And So on and So Forth

There are, as you might imagine, many other explanations.

Group Exercise II

Interpreting the Data II

In your small group, connect some of the demographic patterns you uncovered in Part I of this exercise to cultural factors that might

explain Trumpism on the demand side.

See You on Monday

References

Note: Scroll to access the entire bibliography